If you have never seen the film “Never Let Me Go,” based on Kazuo Ishiguru’s novel of the same name, GO WATCH IT NOW. Yes, right now. I’ll wait. If you are my mother, bring a box of Kleenex. Okay, maybe two.

I love this film so much. SO MUCH. I’ve watched this thing over and over again because I love everything about it: the story, the emotion, the tension, the lurking metaphors, the set dressing, the costumes, the entire aesthetic. Certain critics called this film “hipster sci-fi” (which, as far as epithets go, is basically a compliment). And sure, the very subtle sci-fi alternate history plot, intercut with attractive twentysomethings exchanging longing gazes, having general angst and wearing thrift-shop clothes could easily be written off as a cheap play to that particular demographic.

But actually, it’s not. And what is so interesting about the production design of this film is that Ishiguru’s novel contains very few specific visual details of character and setting. The aesthetic choices that the production team made on this film were bang-on — eerily beautiful visual details to captured the tone of Ishiguru’s chilling first-person narrative, creating a film that actually looked as believable and heart-wrenching as the book felt. The fact that the result was not only stunning but also pretty fashionable was coincidental.

~~~~~~~~~~~~SPOILER ALERT ~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So what is this film about? The premise is this: in the 1950s a singularity occurred. That singularity was the development of human cloning, and thereby the end of disease. The characters in the film, who start out as children in the mid 1970s, are clones who are being raised to donate their organs before the age of 30. They live at a pleasant boarding school called Hailsham where they are taught reading, writing and arithmetic like all children. They do role-playing exercises to learn how to interact with the outside world. And they are encouraged to express themselves artistically, for the faculty of Hailsham are interested in more than simply the care and feeding of clones: they wish to discover whether the clones have souls.

The premise is horrifying and chilling, and becomes even more so as the story progresses because it remains virtually undiscussed, tainting every moment of the characters’ lives. The story is not a revelatory thriller: the characters know their fate and they do not try to escape it. It’s like Logan’s Run… except nobody runs. And there is nowhere to run, just like there is nowhere for any of us to run when it comes down to the end of our lives.

But this film addresses something more specific than the universal anxieties of existence and death. The generational aspect of the film is hard to ignore: the older generation cannibalizes the younger. And this is precisely the direction that the world is taking, albeit in less visceral and more insidious ways. Health care systems are becoming more and more overburdened as older generations live longer. Pension funds are being drained, not only because there are fewer young workers to pay into government pensions, but because those young workers face fewer opportunities, lower comparative wages, higher prices and less job security than their parents and grandparents did. And perhaps worst of all, governments like Canada are stripping the very institutions and organizations dedicated to preserving the integrity of our society and environment for future generations, and investing in military might, unethical and unsafe industrial development, and a political climate of secrecy and control.

So let’s look at some of the ways these profoundly unsettling themes come through in the visual details.

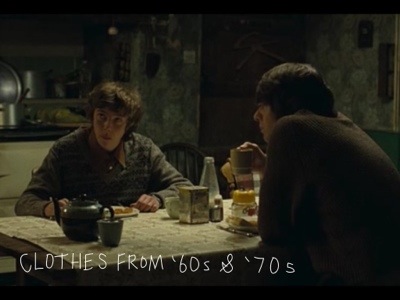

1. Secondhand clothes The children of Hailsham do not have matching uniforms. The boys and girls all wear grey shirts and sweaters and jackets and pinafores, but they are all different, as if they had been color-filtered out of a big bin of secondhand clothes. Now, all schoolchildren, public or private, wear matching uniforms in Britain, so this styling choice highlights two very important plot points: 1) That the students of Hailsham are seen by government (which funds the institution) as second-rate, and 2) That the faculty of Hailsham look at each child as an individual. Even when they grow up, the characters wear clothes just like you or I might find at the local Salvation Army. No one is investing in their future; they have no future, and their lives are simply a means to an end. Why waste valuable resources on them when a bare minimum will do?

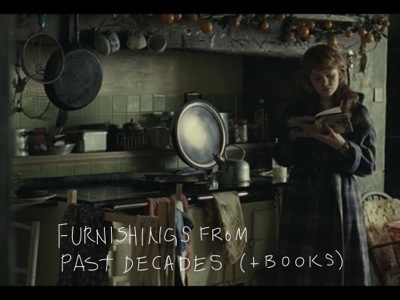

2. Living spaces in disrepair The cracking plaster in the Hailsham dormitory, the uninsulated Cottages and the old, dusty furniture inside reinforce the lack of responsibility that the government feels towards what is really their most valuable commodity. It also indicates that a paradigm shift is taking place. Barely hinted at in the film (and only slightly more in the book) is the fact that Hailsham is unique: there are other homes, referred to as “battery farms”, where conditions are supposedly much more unpleasant. Hailsham’s closure later in the film intimates that the practice of treating clones like real people is to be replaced by cheaper, more efficient methods.

3. Found objects It has been documented that children who grow up in un-rooted, high-stress environments (ie. orphanages) tend to collect and hoard small objects, in an effect to exert control and create for themselves a little nested life amidst the fear and confusion of their worlds. The children of Hailsham are treated to occasional “bumper crops” — the delivery of small secondhand items which they can exchange for tokens garnered for good behavior. Sad little broken dolls, used crayons — the cast-offs of the outside world — become to them sacred treasures to hold and keep for all time. These intrinsically worthless items are carried with the children as they leave the school and spend their few short years living adult lives. Though they are never allowed the responsibility of owning expensive things, they prove that they are worthy, sensitive beings.

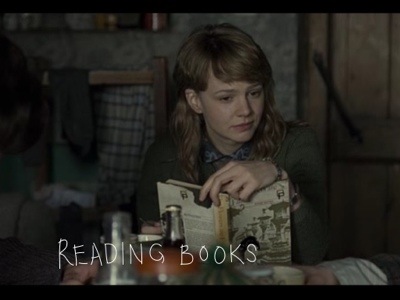

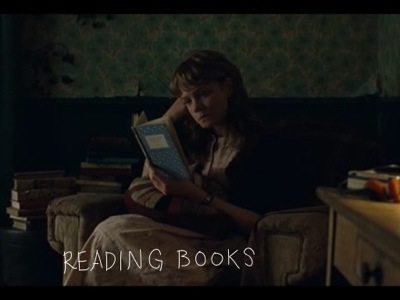

4. Reading books The result of a decent education and artistic encouragement are young adults who are thoughtful, articulate and intelligent human beings, who (just like many young university students) read and learn without any guarantee of future opportunities to put their knowledge to use. And for the clones, their future is to be butchered and used only for their organs, throwing away all the inherent potential that never has time to blossom.