After happening upon about 36 hours of video of Buckminster Fuller lectures from the 1970s, digitized from tape, on YouTube the other day (thanks, GnosticMedia!), I couldn’t help but think about how hard the architect, philosopher, designer and futurist would have shit his pants if he could see the world I live in.

After happening upon about 36 hours of video of Buckminster Fuller lectures from the 1970s, digitized from tape, on YouTube the other day (thanks, GnosticMedia!), I couldn’t help but think about how hard the architect, philosopher, designer and futurist would have shit his pants if he could see the world I live in.

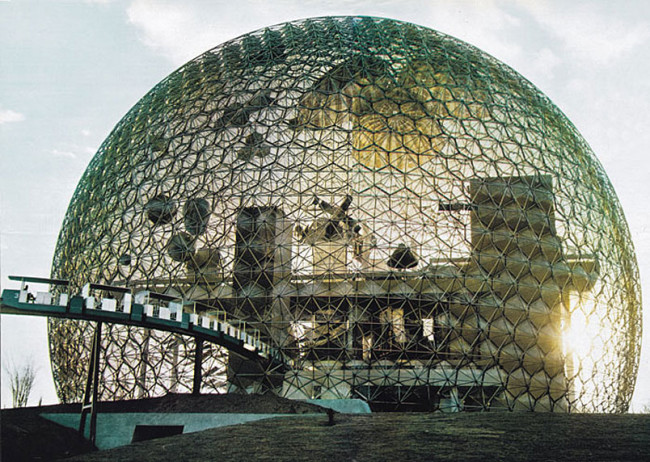

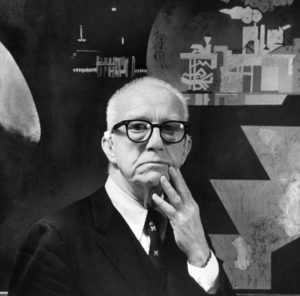

If you’ve never heard of Buckminster Fuller (or Bucky, as he was known), don’t feel bad; he’s most well-known for his work with geodesic domes and doesn’t seem to get a lot of attention outside of the design field. He was born in 1895 and died in 1983, a year before I was born, and was shaped by the unprecedented breakneck pace of change of the twentieth century. He was a true interdisciplinarian, a non-conformist, a man of letters and ideas, able to understand and communicate the overarching narrative of history as he had lived it.

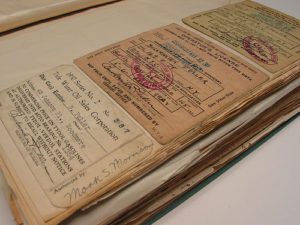

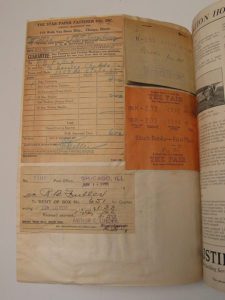

He also kept the most insanely meticulous journal of a human life ever created. This journal, in which (according to Wikipedia) he documented every mundane detail of his life every 15 minutes from 1920 to 1983, came to be known as the Dymaxion Chronofile:

“The Dymaxion Chronofile is Buckminster Fuller‘s attempt to document his life as completely as possible. He created a very large scrapbook in which he documented his life every 15 minutes from 1920 to 1983. The scrapbook contains copies of all correspondence, bills, notes, sketches, and clippings from newspapers. The total collection is estimated to be 270 feet (80 m) worth of paper. This is said to be the most documented human life in history.” (Wikipedia)

“If somebody kept a very accurate record of a human being, going through the era from the Gay ’90s, from a very different kind of world through the turn of the century—as far into the twentieth century as you might live. I decided to make myself a good case history of such a human being and it meant that I could not be judge of what was valid to put in or not. I must put everything in, so I started a very rigorous record.”

– Buckminster Fuller, Oregon Lecture #9, p.324, 12 July 1962

[columns]

[/columns]

Bucky spent his early years getting expelled from Harvard twice, flitting from job to job, working with machines and going bankrupt. In his thirties he decided to buckle down and “search for the principles governing the universe and help advance the evolution of humanity in accordance with them… finding ways of doing more with less to the end that all people everywhere can have more and more.” He wrote a bathtub full of books and spent much of his life working on developing methods of cheap, sustainable housing and transportation.

He believed firmly in the power of one person not only to influence the world, but to steer the entire course of the future (his headstone reads “Call me Trim Tab” — a trimtab is a tiny moving part on a wing or a rudder that directs the whole device with the smallest of movements). And it seems as though he felt an intense obligation to history and record-keeping and had a prescient idea of the value of information in the future, which led to his obsession with documenting his life.

The journals themselves are fantastic pieces of artistic and literary value and I think Bucky would have been delighted with our ability to digitize analogue artifacts and disseminate them with very little time, energy or cost to everyone in the entire world who can get access to an Internet connection. I imagine that if he were still alive, he would have changed and adapted and embraced the world as we know it in 2013, and revelled in our capacity to do so much more with less.

But when I went googling, appreciating my position as an armchair knowledge sponge with instant access to more information than Bucky could have imagined, I found something shocking: the Buckminster Fuller Institute, second hit after Wikipedia, had forgotten to pay its hosting company (it’s now back up and worth a visit), and Stanford University, holder of the Chronofile, uses a Flash gallery unviewable on devices.

Sad trombone. In a world where currency transactions are instant and an eight-year-old can build a website, how can this possibly happen? Have we come over the speed bump of the twentieth century only to be stymied by trivialities? Now that we have found so many ways to do more with less, are we now trying to find out how little we can do before imploding as a global civilization?

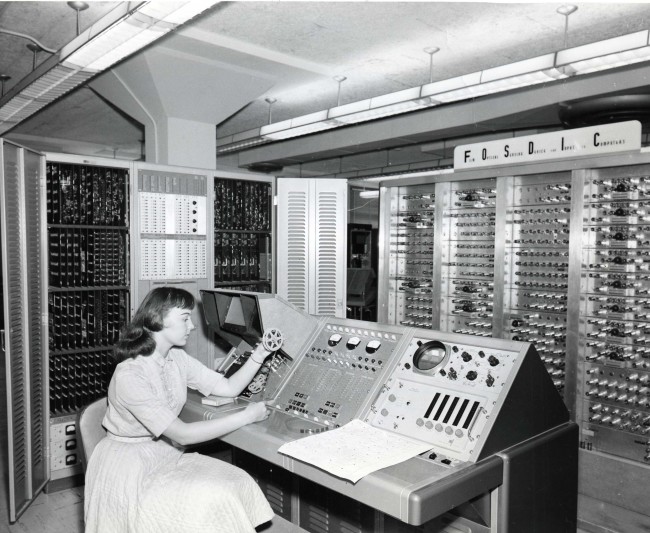

My smartphone — the one I have to coat in plastic and rubber because I’m clumsier than a greased-up toddler — is more powerful than the most expensive military-grade bachelor-apartment-sized computer available in Bucky’s day. My desktop computer could run like 10 nuclear research centres in the 1960s. I can fly to places in a few hours that would have taken months to reach a century ago. With a couple of clicks I can get a ground level panoramic view of any street in the world, download and watch any piece of media ever created, and have anything I could possibly want delivered to my door in a few days. With all that shit handled, you’d imagine we’d have more time for solving problems.

And we do. More people in the world are healthier, cleaner, better educated and richer than ever before in the history of the planet. However much I bitch about the Harper government and world politics and current events, I will have a much better life than almost every woman who lived before me. Sometimes I feel bad, given my privileged position, about the amount of time I spend looking at cat pictures and watching reality tv shows and documenting all the inane details of my life on Facebook.

But I imagine people must have thought Bucky was wasting his time with his Chronofile, noting his hygiene habits and pasting in his train tickets and receipts. The technological history of the past 500 years of human civilization is about overcoming the problems of documenting, storing, duplicating and disseminating information. We’ve gotten so good at recording knowledge that we’re doing it all day, every day, in real time. The issue of corporate data collection currently has newsworthy ethical problems, but think about it in a scientific way: a significant proportion of the eight billion people on this planet are generating numerous packets of recorded, cheaply store-able information every day. This is more information than could ever be optimally grasped and utilized by our civilization, ever. We have so much information that we pay people to get rid of it.

These days, there seems to be a pervasive attitude of trivialization among older, educated people when it comes to new media and things like Facebook and internet culture. But are exponentially-increasing leisure time, computer literacy and global interconnectivity — results of our reliance on computers to collect and analyze data — really the hallmarks of a post-peak society hurtling towards self-induced apocalypse? Every generation seems to disparage the next, but the truth is that human history has been developing in new and highly unpredictable ways for millenia, and some people are uncomfortable with change — and, I suppose, with the idea that a journal or a Facebook profile might be the only faded imprint of your life after you’re gone.

When I think of the changes that took place within Bucky’s lifetime — nearly everything we know about the origin of the human species and composition of the universe, the human brain, space and flight, the development and ubiquitous integration of digital technology — how can I not expect that the world I know now will be ancient and unrecognizable by the time I live out my (astoundingly lengthy, comparatively) life expectancy? We have the chance to participate in a world that’s changing faster than at any other time in the past, and we each have the ability to contribute to the collection and understanding of the world’s store of information from our desk chairs. And we all have a responsibility to take advantage of the technology that has grown from the work of the generations that came before, instead of opining for a nostalgic version of the past that may never have existed.

So be an armchair explorer. Be grateful for your smartphone. Learn how to participate in the changing cultural, intellectual and technological landscape of the world we live in. And don’t take it for granted, because if there is an afterlife, you can bet your balls that Plato and Descartes and Galileo and Newton and all the other human pillars of civilization are looking down on us from the big Tavern in the Sky, green with envy.